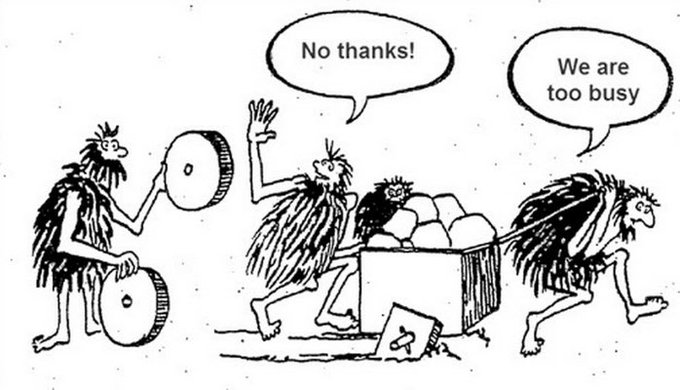

Way back when I blogged about why it’s utterly unrealistic to think that a training is going to turn anyone into a superhero.

That idea is just an all too comfortable thought for organisations that send their staff to training courses.

It feels like they’re ‘capacitating’ their staff. They’re burning budget on it. Box ticked. Staff trained. Job done. Ready to take on the world.

The staff themselves are happy to have some time away from the office, doing something different and ideally in line with what they are doing. It all looks great.

And yet all too often masses of days spent on training are wasted. TOTALLY wasted. An endless series of cases of ‘get trained and blissfully get back to business as usual’… 😦

Sometimes it’s just because there’s no match between the training and the staff. The training does not cover the right content for the staff, or it’s not what they wanted to be trained on. Indeed it does happen, all too often also, that staff are sent on unsolicited training. It could be that the content of the training is relevant but delivered very poorly and thus not very usable. Or sometimes the way the content can be applied to the staff’s day-to-day work seems very far-fetched because very disconnected from that day-to-day reality.

What happens when the training seems a perfect fit then?

But let’s even park all of that and look at a training course that is relevant, solicited by the staff, delivered beautifully and with a wide and obvious relevance for day-to-day work.

Even then, the staff faces a myriad of obstacles to making the training an exciting reality. And these obstacles are both inherent to the staff themselves, or to the environment in which the staff is operating. We’re going to look at these obstacles, and what can be done about it.

But at this point already, it’s clear that a training course is NOT the destination. It’s the rocket launcher. And what matters is that the rocket is sent into orbit. Otherwise, instead of a rocket, it’s another training turning out to be a wet firecracker.

Personal and surrounding barriers to transformation?

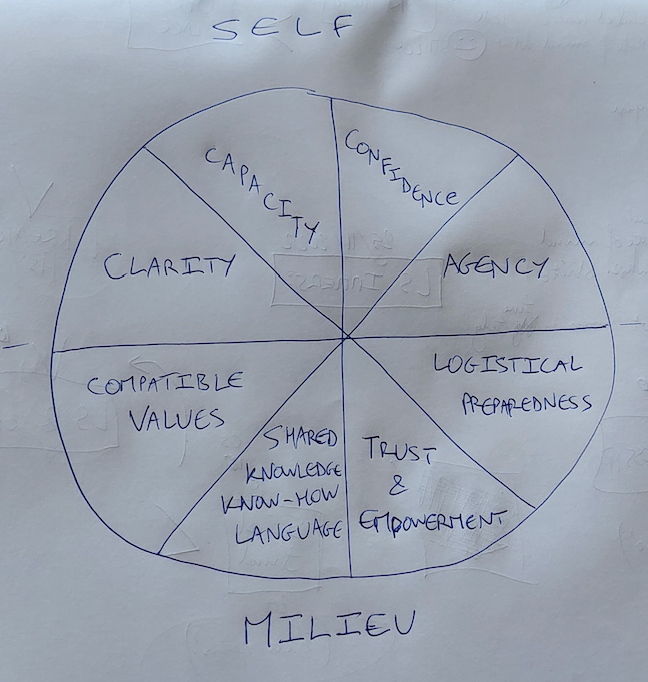

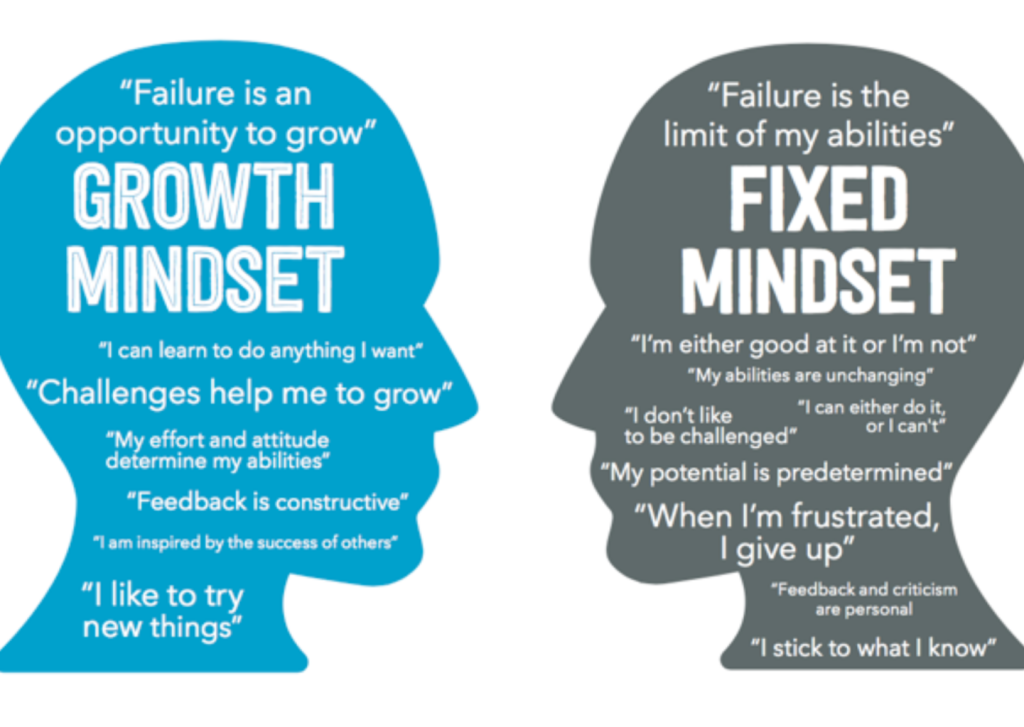

The figure below, let’s playfully call it the wheel of post-training change, shows 8 potential barriers – 4 that relate directly to the individual staff being trained and 4 that relate to their milieu, ie. the environment in which they would/could/can/will apply the results of their training.

Let’s unpack each of these barriers briefly.

The central assumption here is that the training has been valuable and it holds the promise of some change that the individual can bring about to their milieu.

Barriers of the self: “I can’t make it!“

- Clarity: Is the value of the training sufficiently strong and enticing for the staff to actively seek change? Maybe the training was relevant, and interesting, but maybe it was just a ‘nice to have, thank you very much’, not a ‘wow, I see things in a totally different light now!!!” If that clarity is not there, change will be dead in the water.

- Capacity: Has the training provided sufficient knowledge and know-how to equip the staff with what it takes to make change happen. One typical barrier that I see for instance in Liberating Structures immersions with this is that the acticipants get to experience only about 12-15 structures out of the original 33 (let alone as many in development) and that can leave them with a feeling of insufficient capacity or insufficient ‘overview’ of the options that the training gives them.

- Agency: Does the staff have opportunities to apply the fruits of the training? Do they have the time, green lights of the powers-that-be, ‘safe fail’ space to experiment and shape that change, entitlement to scale it up and bring it to another, higher/deeper/wider level in the milieu?

- Confidence: Confidence is critical and it’s usually a reflection of the past three factors. How much trust do you have in yourself to try out what you learned in the training in your day-to-day work?

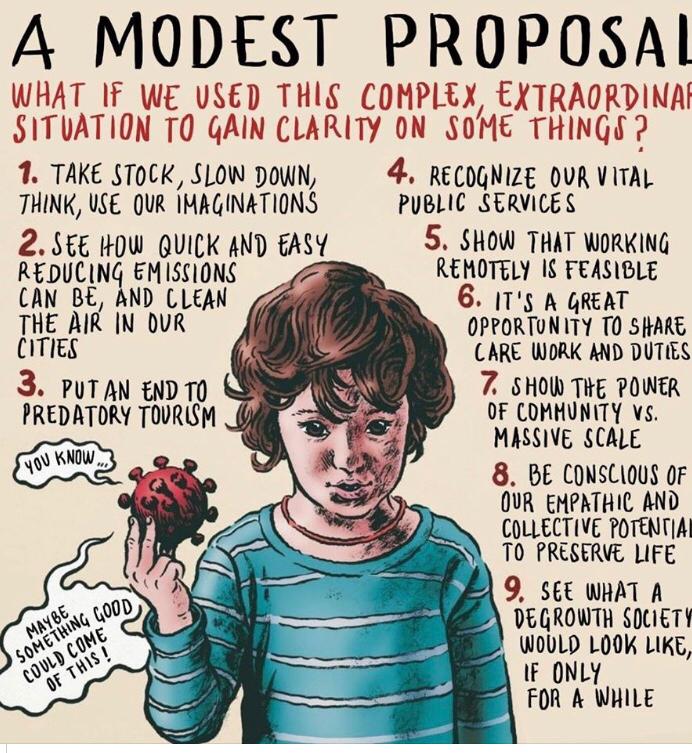

Barriers of the milieu: “They won’t let me!”

- Compatible values: This is the ‘philosophical preparedness’ of the milieu to receive the fruits of the training. How are the organisational values aligned with what the training stands for. Especially if the training pertains to distributing power, decision-making, voice, presence. Does that sit well with management? With direct colleagues? With the rest of the organisation? Is it a fit or are you (trainee) coming back from another planet and your solar system is way too far from planet hope?

- Shared knowledge, know-how, language: This relates to the technical preparedness of the milieu. Does the staff find a fertile ground where other colleagues either understand the technical contents of the training you’ve just followed – maybe they even followed the same – and is it easy to explain what you’ve just done, or you feel like a martian talking to earthlings without much hope for establishing a deep connection?

- Trust and empowerment: Pendant to the confidence of the staff, is direct management, and higher management in a general stance of ‘leading from behind’ and empowering, or rather commanding and controlling? How much does the milieu trust its staffs to bring the best of themselves in the collective interest?

- Logistical preparedness: Finally, are there, in addition to the trained staff’s direct opportunities, other chances to see the contents of the training being tested/applied? And perhaps there is a question of equipment (materials, props etc.) that might be needed in order to put teachings in practice?

All these barriers are real and can impact how a staff is able to apply the contents of their training or not.

In a subsequent post I’ll unpack what can be some options for each of these barriers, feel free to share yours here as a comment, in any case.

Our personal journey of supporting transformation

This whole crux of seeing a training course no longer as a destination and more as a springboard is what is guiding the efforts of Nadia von Holzen and me to support the change-makers out there. We will keep offering trainings such as the upcoming Liberating Structures immersion in June-July 2023 but we are now actively seeking to understand and support change-makers to transform their milieu beyond a simple training course.

If you are one of these change-makers, and are seeking ideas, a sounding board, a ranting recipient, a source of fire with warmth and inspiration, please feel free to contact us (processchangelb [at] gmail.com / nvonholzen [at] gmail.com

A new dawn of collaboration through a double-lens perspective (photo credit: Eleonora Albasi / FlickR)

A new dawn of collaboration through a double-lens perspective (photo credit: Eleonora Albasi / FlickR)